Porto Bridge Disaster 1809

During the Invasion of Portugal by the Napoleonic troops under Marshal Soult in March 1908 they attacked and captured Porto. In their haste to get away thousands of fleeing refugees drowned when the pontoon bridge that crossed the river Douro, collapsed. Bernard Cornwell in his book Sharpe's Havoc wrote about the disaster. Anyone going to Porto should read his book. This is an extract.

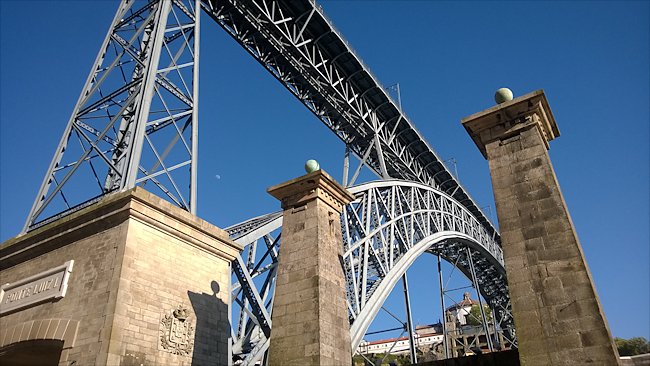

Look out for this commemorative plaque depicting the disaster of 1809 on the Ribeira waterfront near the King Luis I Iron Bridge

In the middle of the river, halfway across the bridge, the Portuguese engineers had inserted a drawbridge so that wine barges and other small craft could go upriver.

The drawbridge spanned the widest gap between any of the pontoons and it was built of heavy oak beams overlaid with oak planks and it was drawn upwards by a pair of windlasses that hauled on ropes through pulleys mounted on a pair of thick timber posts stoutly buttressed with iron struts.

The whole mechanism was ponderously heavy and the drawbridge span was wide and the engineers, mindful of the contraption's weight, had posted notices at either end of the bridge decreeing that only one wagon, carriage or gun team could use the drawbridge at any one time, but now the roadway was so crowded with refugees that the two pontoons supporting the drawbridge's heavy span were sinking under the weight.

This bridge replaced the pontoon bridge that collapsed causing the high lose of life. The plaque is nearby.

The pontoons, like all ships, leaked, and there should have been men aboard to pump out their bilges, but those men had fled with the rest and the weight of the crowd and the slow leaking of the barges meant that the bridge inched lower and lower until the central pontoons, both of them massive barges, were entirely under water and the fast-flowing river began to break and fret against the roadway's edge.

The people there screamed and some of them froze and still more folk pushed on from the northern bank, and then the central part of the roadway slowly dipped beneath the grey water as the people behind forced more fugitives onto the vanished drawbridge which sank even lower.

The central hundred feet of the bridge were now under water. Those hundred feet had been swept clear of people, but more were being forced into the gap that suddenly churned white as the drawbridge was sheared away from the rest of the bridge by the river's pressure.

The great span of the bridge reared up black, turned over and was swept seawards, and now there was no bridge across the Douro, but the people on the northern bank still did not know the roadway was cut and so they kept pushing and bullying their way onto the sagging bridge and those in front could not hold them back and instead were inexorably pushed into the broken gap where the white water seethed on the bridge's shattered ends.

The cries of the crowd grew louder, and the sound only increased the panic so that more and more people struggled towards the place where the refugees drowned. Gun smoke, driven by an errant gust of wind, dipped into the gorge and whirled above the bridge's broken centre where desperate people thrashed at the water as they were swept downstream. Gulls screamed and wheeled.

Some Portuguese troops were now trying to hold the French in the streets of the city, but it was a hopeless endeavour. They were outnumbered, the enemy had the high ground, and more and more French forces were coming down the hill. The screams of the fugitives on the bridge were like the sound of the doomed on the Day of Judgment, the cannonballs were booming overhead, the streets of the city were ringing with musket shots, hooves were echoing from house walls and flames were crackling in buildings broken apart by cannon fire.

But the men manning the barges had rowed themselves to the south bank and abandoned their craft and so there were no boats to rescue the drowning, just horror in a cold grey river

Recommended books